中新網重慶新聞11月29日電(記者 劉賢)中國品牌商品(哥倫比亞)展近日在哥倫比亞首都波哥大市國際會展中心開幕。40多個“中國品牌”中,有重慶海扶的“聚焦超聲消融手術設備”等具有完全自主知識產權的“中國原創”設備及技術。28日,中新網記者在重慶專訪參展企業負責人,挖掘“中國品牌”出海故事。

記者從重慶市商務委員會獲悉,應商務部邀請并經重慶市政府同意,重慶市作為本屆展會的中方主賓市,在展會期間舉辦了“重慶館開館儀式”“重慶主賓市推介會暨簽約儀式”“中國(重慶)與哥倫比亞區域合作論壇和企業一對一對接會”等系列活動。重慶海扶醫療科技、長安汽車、小康汽車、雅鏤園林城建、大足五金刀具等20多家企業近60余人攜拳頭產品參加總面積達700平方米的重慶主賓市展館。會上,重慶市有關區縣、企業還與哥方現場簽署了5項合作協議,涉及投資貿易、互聯互通、友好交流等領域。展會期間,重慶長安汽車還與哥方企業達成550輛整車出口合同。

從“中國制造”到“中國品牌”,兩字之變,卻是一段漫長而艱苦的奮斗歷程。

“改革開放41年,中國人不容易。”聚焦超聲消融手術設備海扶刀®的發明者、重慶海扶醫療科技有限公司董事長王智彪教授接受中新網記者專訪時說,“早期我們更多的是學習西方發達國家的先進技術,主要制造銷售零部件、制成品,處于產業鏈的中下游,很少有自己的品牌。伴隨著改革開放,中國的科學家獲得發展機會,逐漸有了自己的核心技術。”

記者了解到,19世紀50年代,美國科學家提出聚焦超聲治療的想法,但因影像監控等技術不成熟而未能實現。20世紀80年代,中國重慶醫科大學團隊自主研發出海扶刀®聚焦超聲腫瘤系統,并在此后成立重慶海扶醫療科技股份有限公司(簡稱海扶醫療)推動技術轉化,先后獲得中國國家技術發明獎二等獎、中國國家科技進步獎二等獎等獎項。

王智彪說,從研創海扶刀®到現在的31年中,“我們強烈地感受到建立中國品牌的艱辛”。當時,中國原創技術在世界上少見,尤其是醫療健康領域。經過不懈努力,海扶刀®進入英國牛津大學,幫助其探索聚焦超聲消融技術治療子宮肌瘤、肝癌、胰腺癌、骨癌、腎癌等。當地醫生也逐漸轉變認識,認可了中國醫療設備可以造福英國民眾。

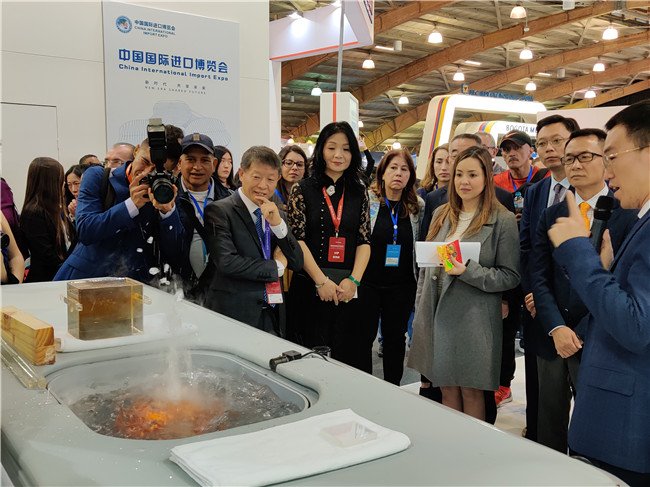

在此次中國品牌商品(哥倫比亞)展上,當地民眾也對中國原創的海扶刀®頗為關注。王智彪說,海扶刀®的展臺200多平方米,除了在重慶館展示模型機,還另有真機展示,以及視頻解說和演示。不少展覽參觀者來詢問腫瘤治療方法。還有當地議會所屬的雜志專門采訪這一“中國品牌”能在公共衛生健康領域發揮哪些作用。

重慶醫科大學教授、海扶醫療國際學術負責人邢若曦告訴記者,在拉丁美洲,海扶刀®已在古巴、多米尼克、阿根廷應用,設有海扶®中心。截至目前,海扶刀®聚焦超聲腫瘤治療系統已獲得歐盟CE認證以及38個國家和地區的準入,在26個國家和地區建立了200多家治療良、惡性腫瘤的臨床應用中心。亞太腹腔鏡協會、歐洲腹腔鏡協會等微無創領域國際權威協會,已經與海扶醫療形成戰略合作關系,共同推廣聚焦超聲消融手術這一造福病人的“無創手術”,推動醫學從“微創”向“無創”邁進。海扶醫療將進一步到“一帶一路”沿線國家推廣,不僅輸出海扶刀®和聚焦超聲治療技術,還要培養當地醫生熟練掌握該技術,讓中國原創技術幫助當地提升公共衛生水平,惠及更多民眾。

從一臺設備、一項技術到一個品牌,海扶®的31年是中國許多原創技術企業“品牌化”的一個縮影。

王智彪說,這個過程很艱難,期間得到重慶市政府及相關部門大力支持。重慶是很美好的城市,讓海扶®得以成長。他期待政府給予更多“中國品牌”重點支持,讓更多“中國品牌”走出去、造福全世界。正如他對哥倫比亞媒體所說:“中國企業不是來推銷一個設備,而是在推廣醫學文明,讓哥倫比亞人民能享受到無創治療腫瘤的新技術,得到有溫度、有情感的治療,重獲健康的希望。”